The Pace of Immigration

Last month I turned seventy-five and (among other things), realized that the New Zealand I grew up in bears only some relationship to the Aotearoa I now try to understand. Not only that, but the society I now live in, seems to be changing at an increasing rate.

Apart from the ever-advancing technologies, many of the changes seem to stem from the increasing number of people arriving on our shores, from all round the world. Not that this is anything new. I heard a story once, many years ago, about Waru sitting in his waka in Waitemata harbour watching the latest passenger ship coming in from England, wondering why the Pakeha didn’t just stay where they came from. Some things don’t change as much as we might think.

Over-population, while causing considerable stress in many other parts of the world, is not regarded by many as being a major problem for us, here, yet. Nearing five million people isn’t a big deal given the size of our country, relative to other places in the world. The pace of growth, though, is causing issues which could get worse if we don’t recognize them, and do something about it.

Immigration requires more infrastructure growth and increased housing but at a speed that can be handled. Too many people arriving too quickly, results in not enough housing to go around. Not only does housing need to be upped, but social infrastructure such as water, sewerage, waste disposal etc. needs also to keep pace. Current media headlines suggests this is not happening in a number of cities. Homelessness is probably the most obvious result of an overly fast immigration rate, but not the only one.

People from other countries have differing value sets and strongly held belief systems, often leading to very different social expectations. This phenomenon also needs to be recognized and accommodated peacefully as immigration increases. Our country’s social systems with its associated beliefs and values, built up over the last two centuries and cherished by existing New Zealanders, are likely to face testing times. If immigration happens too quickly, troubles will most likely spring up.

It is difficult to address the full complexity of these issues if there is a lack of systems-wide understanding by the general community and political parties, of the total picture. “We need more trained workers: we need more houses: we need faster economic growth: etc, etc.” All may be valid to a point, but each argument on its own doesn’t always stack up when the total picture of a healthy national community is what we are really striving for. Concentrating on one issue on its own, without taking into account the total picture, is a recipe for failure. Families having to sleep in cars is today’s sign of this kind of failure.

Obviously a common set of values and beliefs isn’t going to happen overnight, if ever. Even getting a modicum of acceptance takes time; centuries in some cases. Anyone with more than a passing knowledge of the social history of the UK, for example, knows it took thousands of years and many wars and substantial changes in social structures to get where they are today. Taking things faster than can be accommodated, is a recipe for a very unhealthy society. (Some would say that is happening again now in the UK, with Brexit, but that’s another story).

In our own country today, for example, much is still heard of the need for bi-culturalism. With high rates of immigration from many countries, we are now facing the question of what New Zealand as a multi-cultural society might look like.

As the saying goes, “we live in an ever-changing world”. Regulating the pace of immigration to a level that keeps a changing, but relatively integrated society healthy, is a must. Our challenge is to change without trying to go too fast; finding the right balance while aiming for the development of a socially healthy community. That’s what we should be aiming for.

Upon this Rock a religion was built

Bible-reading Christians will know that Jesus was credited with appointing Saint Peter as the rock on which his church would be built. Over the last two centuries, a new religion has sprung up and spread around the world; industrialism and associated capitalism, based on the rock of cheap, available, fossil fuels. It started in England, with the development of steam engines burning coal, initially to drain water out of tin mines in Cornwall. The new technology grew quickly to power, among other things, steam engines, in trains and large industrial factories. When cheap crude oil was discovered, the pace of the development of the new religion picked up.

All this needed capital, so over time, various banks and stock exchanges were created, followed by companies that were eventually accorded by law, the status of human beings.

The new religion was in place, based on the ‘rock’ of fossil fuels.

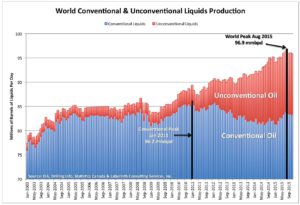

Unfortunately for the new religion and its adherents, the ‘rock’, cheap fossil fuels, is now beginning to Peter out, becoming, in fits and starts, more expensive to produce, to the point where world-wide, industries are starting to feel the economic pinch, beginning in the higher-cost ‘Western world’ countries where the religion started. Conventional crude oil, produced by simply drilling a hole and getting oil to naturally gush out, peaked in the USA in the early 1970’s. Conventional crude oil appears to have plateaued worldwide, in 2008. (Google and the internet has many credible charts on oil world production. See above graph).

While production costs in many Middle Eastern countries remain at about $US10 /barrel, the fossil fuel pulpit has been challenged by ‘fracked’ oil concentrates and oil from tar-sands. However, the cost per barrel of fracked oil is about $US40 in the ‘sweeter’ areas, going up to over $US70 in the ‘harder to get’ areas. Oil-sand oil is also relatively expensive to produce.

As fossil fuels become more expensive to produce, goods produced from their use become more expensive causing demand to decrease and industries to close down. More and more people are finding themselves out of the traditional forms of work which we have become used to having. Economic growth crumbles as demand drops off due to the combination of lower (or no) wages and higher prices for goods and services. Without economic growth (or at least the way it’s measured) the whole structure of the religion of industrial capitalism begins to crumble.

As with all religions, the industrialism and associated capitalism religion will not die easily. As ill-informed and/or uninformed people and politicians react to the often negative changes occurring world-wide, previously unthinkable things begin to happen. We are already seeing the two great empirical nations of the last two hundred years, the US and the UK starting to come apart. Who knows what will happen in these two countries. Only the brave and/or foolish would predict their futures. As corporations took on human status, now it’s rivers (at least in New Zealand and India), albeit probably a better long-term bet.

The one positive aspect of all this is that global warming will be affected, positively, even if experts tell us it wont happen fast enough. But that’s another blog topic for some future time.

New Zealand and the Big Bear

New Zealand and the Big Bear.

Yesterday my wife and I drove over to the Wairarapa from Plimmerton. It was Saturday afternoon and we were amazed at how much traffic there was on the road. It wasn’t even a nice day for travelling: the weather was lousy. I couldn’t help but think about all the global-warming CO2 that was being pumped into the air by the traffic, our car including. Not that a small country like NZ can be accused of being a major contributor to world global warming, but we do pride ourselves on doing our bit in international affairs.

A quick look on the NZ Stats dept. website, plus a couple of phone calls, indicated that our global warming contribution per person is not good, and is not improving. The two main contributors are agriculture at 48% of the total, and energy (mainly transport fuels) at 40.6%. If, as a country, we want to seriously reduce our contribution to getting a cage around the Big Bear, farming and transport will need to take bit hits.

The next morning the media were full of the damage an over-night storm, with in some cases record rainfall, had caused around the country. It’s not possible to seriously ascribe the cause of a single weather event to global warming, there have to be a number, showing a pattern. However, the pattern seems to be developing, and climate scientists keep telling us that a warmer atmosphere leads to more water being able to be stored, leading to heavier rainfall, incidences. So we can be fairly certain we’re going to see an increase in damage caused along with an increase in the cost of fixing infrastructure.

Farmers, especially dairy farmers, are coming under increased pressure to stop fouling water-ways, but a 48% contribution to global warming is another major issue that will need tackling. Individual farmers can’t be blamed as they operate within an economic system which calls for more growth; it has almost become a religious creed. However, from an environmental perspective there is no doubt that NZ agriculture is in ‘over-shoot’, and will get wound back somehow, sometime, unfortunately, as some see it, resulting in less overseas exchange being earned.

So where to from here? People will object to being told to use their cars and trucks less, and no-one wants to see a drop-off in overseas earnings.

There are ways, however to fix things. For example, NZ imports many thousands of tonnes of animal feed each year, to feed farm stock. The bill runs to tens of millions of dollars. If an increasing tax were imposed on these imports, farmers would be forced to stop growing their stock numbers (especially dairy cows) and return to farming based on grass and crops grown in New Zealand. ‘Over-shoot’ would begin to correct itself. (Anyway, when you think about it, we need overseas exchange only to pay for things we want to buy from overseas. Maybe we’re going to have to want less cheap stuff, and start producing things we really need, here in NZ).

An increasing tax on fossil transport fuels would, over time, discourage the use of road transport, reducing road maintenance costs and add to government’s income. The increased taxation could be used to pay for repairs to increasing global warming damage.

I’m not that naive to belief that these suggestions will be picked up by any NZ government in the near future. Voter back-lash would be too great, and voter back-lash is something all politicians steer well clear off. Having said that, it is becoming increasingly clear to people who allow themselves to see, that the big bear has to be caged, or the cost of its claw-gouges will become too much to put up with.

Transport Again

Office Workers at Work

My last posting was about digital technology and how it could be used to improve our well-being. There was reference to traffic issues in major cities and how they might be improved by increased use of internet technology. This last week in the Wellington media, a major story surfaced once again, about how to fix the rush-hour traffic problem. The most interesting part of the story, was an account of the working party being set up to look at the problem (again). The people were mainly from transport-related organisations. This will pretty well guarantee that solutions proposed, will be transport-focused. Not a very good example of what to do in these times of major change.

The issue is that there are too many people and vehicles using the transport system during relatively short periods during the day. The most obvious solution then, is to find ways of reducing the number of users during peak periods, rather than build more transport solutions which cost mega-bucks, and more often than not, only add to the problem. The working party then, should be mainly comprised of people who are not transport-focused, and more likely to look at other possible ways off addressing the issue: how can car-numbers in particular, be reduced during rush-hours.

Just because work-hours in Wellington have historically always started at 8am to 9am, and finish at between 4.30pm and 5pm doesn’t mean they have to continue like that. There are now other ways of managing office staff, for example, than by just making sure they’re at their desk. Not all public servants are needed in Central Wellington at all times. Spending hundreds of millions of dollars keeping this practice going, is a gross waste of money, when there are now, alternatives. But appointing transport people to come up with the alternatives is most unlikely to produce other than very expensive transport-related answers.

There are better ways, not yet widely used around the world, but we keep telling ourselves we’re a smart country, and this is a good opportunity for demonstrating it. Try arguing over this approach, as an example.

The Wellington Regional Council set up a Facebook page asking Wellington workers if they have easy access to quality broadband. (don’t rely on traditional broadband suppliers to supply the answers.) Take account of what is said, and make sure they do get good broadband. There are low-cost ways of delivering it. It doesn’t all have to be delivered by fibre.

Pay the NZ Institute of Management to do work on managers managing on outputs rather than ‘who’s at their desk’ and hold seminars on their findings.

Cajole one or two government departments to set up places for their people to work at least 20 hours a week in nearby suburbs. Porirua with its empty CBD buildings would be a good place to start.

The digital age is here, let’s make use of it for improving our lot: it is possible. These changing times demand changing ways of doing things.

The Digital Age: Disruption or Opportunities?

One of the mega-drivers of change, “New Knowledge”, covers our new digital age, where computers and the internet, if they haven’t already done so, are steadily taking over much of our lives. Frequent media headlines shout out about how jobs are being taken over by increased use of digital devices of one sort or another. New technology displacing jobs is nothing new of course. The beginning of the industrial age saw the emergence of Luddite movement in the UK (see Wikipedia), where people were actually shot for protesting against the introduction of new technology. In my working life, I’ve seen typing pools disappear and cash being replaced by ‘plastic fantastic’ cards and digital money, to name but two changes. I’ve not heard of anyone being shot for protesting. Indeed, now, many people eagerly look forward to the latest digital gadgets coming into the shops, and about 95% of money transactions in developed countries, is in digital form.

I’ve recently had a personal experience of the digital take-over. I’ve just finished having a novel written, printed and self published using technology not available even a few years ago. Even to say I wrote it is a misnomer. I ‘said it’ to a computer program which converted my speech into written text, with fewer mistakes than if I had been doing the typing myself. An independent professional editor, and a small independent printing company did the rest, without going anywhere near the conventional publishing establishment. The hard-copy book is even being sold online by the printer and myself, as well as in bookstores. Those who don’t buy books these days, can even get the story in digital (eBook) form from the book’s printer, “Yourbooks”. (“Flight of the Tui”, if you’re interested. It’ll be out in a couple of weeks, and is a great read, even if I say so myself).

In some aspects of the digital technology uptake, though, as a country we’re proving to be a little backward. City people, as well as central and local government, continue to fill the headlines with traffic problems, especially at rush hour. The arguments and suggested solutions nearly always revolve around transport infrastructure, and literally billions of dollars are being spent, often resulting in traffic jams just being transferred from one part of the system to another. Most of the drivers of the cars are office workers of one sort or another, going from home to work to sit behind a computer all day. They could just as easily be seated behind a computer outside of the various central business districts, nearer to their home, if not at home, for at least three days a week. Better internet technology uptake, changes in management techniques to manage on work output rather than ‘whose behind their desks’ management styles, are now needed to ensure money spent is in the right place, rather than being wasted on major transport infrastructure projects.

Internet technology infrastructure in rural areas is also a far better place to spend money. Small rural towns which lost much of their economic vitality as roads and transport systems improved about sixty years ago, and many employers moved to larger cities, could be revitalized by having wi-fi in homes and small local businesses. Low-cost wireless technology has been around for some time now, enabling this to happen, but it hasn’t been widely taken up. It’s another example of not being as smart as we could be. It’s one thing being able to buy the latest digital gadgets when they hit the shops in the bigger towns and cities, but some people and some places can’t afford to do so, or the technology infrastructure isn’t in place to enable the gadgets to work. Some of the money spent on transport infrastructure would be better spent on digital technology structure, and associated technology learning opportunities. It’s a changing world out there. We can keep up and organize ourselves to take advantage of changes like the digital age. It’s just a matter of seeing the opportunities for improving our collective NZ lifestyles, and carrying out constructive work to make it happen. The choices are ours to make, at all levels of our national society.

The Three Bears

Within the eight mega-drivers of change listed in an earlier blog, there are three of major current concern. They are capable of bringing our relatively ordered world to an end if we humans don’t change our ways over the next decade or so. They are, of course, global warming, population growth and fossil fuel use. Because of their outstanding importance, let’s nick-name them, The Three Bears.

Global warming has long been denied by many, but increasing mention of it in all media around the world, suggests it is increasingly being seen for the monster it is becoming. For those who still doubt the now very large scientific verification of the phenomena, you could well read “Plows, Plagues and Petroleum”, by Richard Ruddiman, first published in 2005. For those who say “global warming is nothing new, it’s happened before,” Ruddiman is able to demonstrate with solid, verified information, that you are right. Looking back over millions of years using ice-core data,and using information about how the earth’s tilt and passage around the sun change over time, it’s clear the earth has been through hotter times than the present. However, using more recent ice-core data, and equating the changes of carbon in the cores with known changes in human activity over the last ten thousand years up until today, Ruddiman is able to demonstrate unequivocally that we humans are now causing the earth to warm to dangerous levels, and if we don’t put a stop to it soon, we wont be able to stop much of the globe becoming uninhabitable.

That’s pretty heavy stuff, but it has been proven to be true.

The second bear is population growth. A Google search will provide all the credible data you need to show that the number of people in the world today at 7.5 billion, is close to, if not over in many areas, the number that can be well fed, housed and looked after in what we now regard is a reasonably civilized manner. Simple arithmetic shows that all families should not have more than an average of two, at the most, three children, if populations are to keep themselves in livable order. Since the start of the industrial era, and associated increased affordable food production, the world’s population has exploded to, or possibly already past the stage where everyone can be properly fed. Humans have to become more disciplined in the number of off-spring they give birth to. If our various laws, cultures and religions do not adapt to take overpopulation into account, this Bear will bite. In some countries, it already has.

The third bear is energy availability and cost. Since 2005, when the supply of cheap conventional crude oil plateaued, the world’s energy markets have been in turmoil. New, unconventional oils using fracking technologies, deep-sea drilling and oil from oil-sands have kept supply up, but at increased cost, both environmentally and financially. At the turn of this century, conventional crude was being obtained from the ground at about $7/barrel, mainly in Saudi Arabia. Then the financial markets panicked, and at one stage the market price rose to over $130/barrel. Since then, it’s been all over the place, currently in the mid $40’s.

Notwithstanding financial shenanigans, there are two fundamental realities, however. The first is that supplies of cheap fossil fuels are ecologically limited. An example is the increasing cost of ever-deepening and reduced quality coal mining which has become uneconomic in most traditional mining regions, leading to coal production ceasing in most of the developed world. All forms of oil appear to be facing the same situation over the short to medium term.

The second reality is that the industrial age in which our societies have evolved and grown over the last two hundred or so years, depends on cheap fossil fuels as the basis of its existance. Without them, the the world’s entire economic, social, and possibly political structures cannot continue to exist in their present forms. The USA and Britain are currently demonstrating that with full force. As with the other two Bears, the Energy Bear has already started to bite.

Many of you reading this blog, will now be convinced I’m a ‘Doomer’. I’m not wholly an optimist when considering the Three Bears and their inter-relationships, but there are ways our societies, (especially our New Zealand society), can adapt, if we’re smart enough, so future generations can all lead reasonable lives.

Keep watching,there’s plenty to talk about.

Doomer or Optimist?

When getting into a group discussion on what the future might hold, often one of the first comments made is “Oh, the world is always changing, what’s so different today?” As the discussion proceeds, I usually get “Oh, you’re just a ‘doomer’. Both comments are probably true on the surface, but if you’ve read and thought about the first posting on this site, the mega-drivers of change, and have done a bit of homework, you will now realise the changes taking place constitute a major disruption to our established world on a scale which happens only once in hundreds, sometimes thousands of years.

The last time this scale of change occurred was arguably about the end of medieval age and the beginning of the industrial age. Yes, the world is always changing, but the difference now is that many established pillars of our industrial society are under threat, and in some cases, crumbling as the world begins to de-industrialize. Established religions together with beliefs and practices, places of work and the types of jobs available, (or not available), most governments and local bodies supplying long-regarded ‘entitlements’ such as infrastructure and social systems (education, health, police forces etc), the political and financial systems, are all now facing very considerable difficulties to deliver what has become expected of them.

Articulating all this over a drink of whatever nature, with friends who haven’t been made aware of the mega-drivers of change now in play, earns the title of “Doomer’.

The challenge of course is to figure out how to handle the changes needed in all societies (remember the change factors are worldwide), while retaining a worthwhile lifestyle based on the societal values we want to retain. Re-designing a new social structure while the old one is crumbling, is not going to be easy, as no-one has come up with a formula for making this happen. Trying to retain the industrial age which has been based on low-cost available fossil fuels, will most likely work for a little longer, (if we forget about global warming) until the coal, gas and oils become too expensive to produce, for most existing uses. However the increasing number of people now unable to financially support themselves because of changes that have already happened in their locality, are becoming increasingly restless, leading to extreme political polarization.

The fact that established political infrastructures, anywhere, do not have answers, only adds to the problem. Unions which once kept ‘Labour’ parties going are becoming fewer where de-industrialization is occurring and have therefore less money and political clout. If things keep going the way they are, business-oriented political parties will no doubt face the same challenges. The democratic form of government we have enjoyed for a long time is coming under increasing pressure to deliver answers in these changing times, answers which no-one has.

So what else is there that has the potential to sort out the evolutionary changes needed for us all to live worthwhile, if probably, somewhat more frugal lives?

There-in lies the problem we have. No-one can be sure about what might work, as we’re talking about the future, and by definition, that hasn’t yet happened. We now have to do what our world has always done: we have to evolve. We have to try out new ways of doing things, discover things that will work and go with them, and discard what wont. That’s the only way we have of finding a good way forward. Trying to retain or regain what we once had, will only see our societies break apart and people grabbing what they can, often with force, to survive. The Middle East is demonstrating for us what that leads to.

We can accept that our social structure is undergoing fundamental change without being ‘Doomers’ if we make greater use of our frontal cortex; do away with some of our existing beliefs and parts of our cultures that no longer fit these hugely changing times. Let’s try out new ideas that could help us in the future, live worthwhile and fruitful lives. We might not always have the ‘stuff’ we’ve become used to, but with luck, we’ll still be able to enjoy ourselves.

The Mega-Drivers of Change

Ten or so years ago, while Chairperson of the then NZ Futures Trust I was lucky enough to be able to form a small group of internationally-recognised futurists, and, after considerable discussion and argument, compile a list of eight winds of change which would have major affects on the world to 2030. Over the last ten years, events have proved we did a pretty good job, as the impacts and consequences of these mega-drivers of change begin to emerge.

The eight megadrivers we identified are as follows.

New Knowledge

This has been selected as a major change driver, as often, when new knowledge combines with a perceived human want or need, new technologies emerge that change tremendously, the way we do things. Recent examples include digital technology fueling computers, the internet and cell phones; the jet engine fueling growth in international travel and tourism; artificial fibre for cheaper, more effective clothing; the list goes on

New Zealand with a small population in an isolated part of the world will benefit from developing new knowledge and identifying early as many convergent opportunities as possible and thus new knowledge will be a major driver of change over the next quarter century.

Water

This has been selected as a major change driver as water is essential for life and is capable in natural and manmade circumstances of destroying communities and economies.

New Zealand as a primary producer and tourist destination will need to continue to ensure that there is an adequate supply of good quality fresh water. It is an increasingly contested resource, and is becoming a significant risk management issue for farmers, dwellers by coasts, on hillsides and on floodplains, local bodies, and transport system operators and insurers. Water quality in rivers, lakes and streams is a mounting and costly societal concern.

Our islands are surrounded by vast oceans of water that will continue to impact on our future. Coastal water management will be a major driver of change over the next quarter century

The Global Economy

The global economic situation is constantly changing and local economies are becoming more and more interdependent. The global economy has since 1970 has been defined by over-productive capacity and vast movements of capital, excess to requirements needing to find a home. Given this overheated economic situation and the considerable movements of capital, there is considerable uncertainty for the coming decades.

The New Zealand economy is deep in debt, and as a nation is very dependent on international trade. The shape of the global economy will be a major driver of change over the next quarter century.

Social Inequalities

Large social inequalities in societies tend to be destabilising and can result in civil war and anarchy. Internationally troublesome social inequalities are becoming more prevalent and the situation may worsen as communities struggle for natural resources that are now becoming scarce and where extreme wealth coexists with poverty

Historically New Zealand had a brief period of several decades of relative social equality (circa 1945-84) but since then for various reasons a wider socio-economic spread has developed and more unacceptable social behavior is being reported.

Changes in wider s social inequalities will be a major driver of change over the next quarter century.

Climate Change

The planet is experiencing a period of more rapid climate change over the whole planet than experienced before in modern human history. The changes appear to be mainly unfavourable for humans and most other life forms as most are unable to adapt their lifestyle rapidly enough to survive.

Scientific evidence suggests that human activity is largely responsible for the increased rate of change. This is a global issue and the future of the planet is going to depend on how we as individuals accept and support solutions, resolve the tensions that will arise as the present population distribution and our personal lifestyles are altered drastically.

New Zealand society and economic well-being is very dependent on stable weather patterns as agriculture is our main economic resource.

Rapidly changing weather patterns will be a major driver of change over the next quarter century.

Belief Systems and Multi-ethnicity

The world population density, ease of travel and for many the personal desire to migrate mean that most communities are no longer isolated and that all communities now have a significant number of people with very different life-experiences and antecedents.

Change in community life is mainly determined by the current belief system of the group. Rapid technology changes and the multiplicity of belief systems within communities is creating tensions and debate that need new social structures for communities to survive and prosper.

New Zealand is a country of migrants with about 20% of its resident population born outside of New Zealand. Our migration policy has led to a very diverse mix of cultures superimposed on the bi-cultural beginnings of the last 150 years of settlement.

How we learn to live together as a multicultural society will be a major driver of change over the next quarter century.

Population Dynamics

Increasing population densities, migrations and population aging are features affecting most countries in some way. They are likely to increase in magnitude over the next twenty years, resulting in major changes to population dynamics and their secondary affects throughout the world. Many developing countries are already unable and/or unable to afford, to feed their populations. Many of these people are seeking better living conditions in other, more developed countries, usually against the wishes of the receiving countries. This condition is unlikely to decrease in the foreseeable future, and could well become more pronounced if/as inequalities continue to grow.

Aging populations in the developed world will have major impacts on the cost of national budgets and change the mix of products and services expected by communities for example in health and housing.

Changing population dynamics will be a major driver of change over the next quarter century.

Energy

There is a strong probability that the international price of oil will increase to historically very high levels over the next decade and will become increasingly unavailable for widespread use, especially for transport.

The economies of the developed world, and much of the developing world, have been underpinned by cheap fossil fuels for nearly a century. The shift from cheap fossil fuels to more expensive, alternative energy sources are likely to have profound impacts on the way individuals live, how national and global economies operate, and the manner in which international affairs are conducted.

Changing energy paradigms will be a major driver of change over the next quarter of a century.